|

Do not knock—Filming.

Will come out between takes" reads the handwritten note taped to Shirley MacLaine's Malibu beach

door. After briefly sitting on the stair well, the photographer and I meander under the eight-unit

orientalesque apartment complex and take a short path that leads to the ocean. It is a dreary day.

Between thunderous waves, we catch glimpses of diving dolphins. Since the fifties, MacLaine has

owned this building and has lived in every apartment. In fact, she once occupied the entire upper floor

of the two-story building, but then she subdivided it. She recently made a permanent move to the

Santa Fe, New Mexico area, but keeps this one apartment as a pied-à-terre. She's in town

because last night she presented Barbra Streisand with a Golden Globe life achievement award.

Dale C. Olson, her publicist for nearly thirty years, lets us in. Shirley is sitting on a chair

in the middle of her modest living room surrounded by cameras, lights, and crew. The rustic, well

lived-in seventies decor is plentiful with lit candles, fresh flowers, crystals, and aromatherapy.

She is being videotaped for a documentary. As I walk in, our eyes meet. Her curious

gaze exudes warmth. She is focused on what she is saying, but is cognizant of the total

environment around her. This happens periodically during our interview. One might think she

is easily distracted, but it has more to do with being acutely attuned.

A section of the living room wall has a collage of framed landmark photographs of Sachi, forty-three,

MacLaine's only child. There is Sachi's wedding, Sachi and her children, and the famous February

1959 Life magazine cover of Shirley and a two-year-old Sachi as they goof it up with a strand

of pearls au natural. On a table is a collection of framed photos including a newspaper

clipping of Jack Nicholson and Shirley kissing after receiving their Oscars, and a Christmas card

signed "the Beatty family"—Warren, Shirely's brother, his wife Annette Bening, and their kids.

The coffee table is draped with several books, The Power of Travel, Societies and Cultures in

World History, and Y2K Survival guide and Cookbook. Off the living room, a balcony

overlooks the ocean and sports a welcome mat—"Welcome to UFOs and their crews."

AS I watch Shirley, her moveis flash before me: The Trouble with Harry, Some Came Running,

Ocean's Eleven, The Apartment, What a Way to Go!, Sweet Charity, The Turning Point, Being There,

Madame Sousatzka, Steel Magnolias, Postcards from the Edge, Used People, and of course

Terms of Endearment, for which she won an Academy Award for Best Acress. It's a wrap—the

crew leaves and before we formally meet, Shirley instantly zeros in on what I'm wearing around my

neck. "What is that?" she quizzically asks touching the braided cord. "The Dalai Lama

wears one." She's intense and genuinely interested.

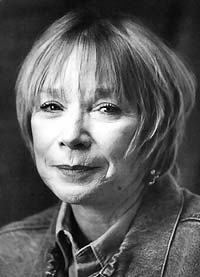

Shirley is casual in faded blue jeans, light blue shirt with jean jacket, white tennies with hot pink

dance socks that bunch around the ankle. On each ear hang five dainty ruby red bells. She

resembles a pixie doll with her expressive eyes, beaming face, and signature shagged red hair.

Her demeanor is that of a kid in a candy store—curiosity mixed with excitement. Author,

actress, dancer, seminar speaker, singer, award winner, video producer, metaphysician, and grandmother.

She is full of life. There is no bull about MacLaine—she's straightforward and honest.

We sit on the well-worn sofa as a giant gilded mirror hangs above. She is somewhat edgy,

understandably so, because of a late night. The rolling waves are constant music that sometimes

make it difficult for us to hear each other.

Shirley is casual in faded blue jeans, light blue shirt with jean jacket, white tennies with hot pink

dance socks that bunch around the ankle. On each ear hang five dainty ruby red bells. She

resembles a pixie doll with her expressive eyes, beaming face, and signature shagged red hair.

Her demeanor is that of a kid in a candy store—curiosity mixed with excitement. Author,

actress, dancer, seminar speaker, singer, award winner, video producer, metaphysician, and grandmother.

She is full of life. There is no bull about MacLaine—she's straightforward and honest.

We sit on the well-worn sofa as a giant gilded mirror hangs above. She is somewhat edgy,

understandably so, because of a late night. The rolling waves are constant music that sometimes

make it difficult for us to hear each other.

"AIDS is a male chauvinist issue," Shirley says matter-of-factly. She heard Elizabeth Reed,

AIDS Representative of the United Nations, make this flat statement and agreed. "AIDS is a

culturally educational problem in these Third World countries. Men go with whomever they want,

then come back and have the right to demand, even through violence, sex with their wives. That's

how everybody keeps getting infected. You can just blanketly say, it's a male chauvinist problem."

Shirley first became aware of AIDS in 1982, when she worked with lyricist Christopher Adler (son of

Richard Adler, who scored the words to her first Boradway show, The Pajama Game) on her one-woman

production. "I used to bounce Christopher on my knee when he was a kid," she remembers.

"He started to cough, and get strangely sick. He stayed with me for a long time out here while we

wrote these lyrics together. Then he went to the hospital and neither of us knew what was wrong.

Couldn't figure it out. Nobody knew what it was! And then within a year he was dead."

Later she spoke to Debbie Reynolds who complained about how many of her dancers were ill.

Shirley knew several friends who had vacationed in Haiti and they were also sick. "And I said,

What the heck is all this about?" she exclaims. "It wasn't just gays, but straights were getting

sick, too. So what became known as a gay disease was not a gay disease." She did research,

discovered it was an immune deficiency and learned they traced it back to Patient Zero, the HIV-positive

flight attendant who transmitted the virus to many men during his travels. Then she read a dire

piece in the Village Voice that screamed about New York having to be cordoned off and quarantined.

"All that fear sprang up. But it did put us in touch with individual rights and what it

means in a culture that's supposed to take care of its own."

Shirley thinks about the friends she's lost to AIDS. "Half of my address book is gone!" she cries.

Colin Higgins, a dear friend who died, didn't tell her for a year that he had AIDS, although he

apologized later for keeping it from her. Colin wrote and directed Harold and Maude and

Foul Play, penned Silver Streak and directed The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas

and 9 to 5 (which he also co-wrote). He assisted MacLaine in adapting her courageous book,

Out On A Limb, for a TV miniseries. "We were shooting in Peru! And I just thought he

had a bacterial infection because he was sick all the time. Although, he was thrilled he was losing

weight because he was very interested in his vanity." After Out On A Limb, Colin began

writing a sequel to 9 to 5, which took place in Washington, D.C. He'd travel there to do

research, he would tell Shirley. Actually, he was visiting the National Institute of Health where

the doctors would mainline AZT into his arm. Eventually, Shirley noticed that he was wearing long

sleeves, which he never did before, but she figured he had changed his style. It wasn't until he

visited MacLaine at her Seattle home that he confided in her. "A bunch of us were undergoing

treatments with a psychic surgeon, and he went last. Then we took a walk and he told me." A

week before Colin died, friends pitched a birthday party for him. He had CMV, and could only see a

pinpoint of light, but he never let on. "He was so dignified and so extraordinarily classy," says

MacLaine. Early in the party Colin needed to go to bed, so Shirley and friends congregated outside

his window for hours singing "Waltzing Matilda." Days later, MacLaine was shooting Steel

Magnolias in the Louisiana heat when all of a sudden she felt dizzy and retreated to her trailer.

She laid down and collapsed. At that moment, Colin died.

Shirley has lost many people, including her parents and lifelong friend, Congresswoman Bella Abzug.

She comments, "Well, a lot of it's because I'm old. And so are they!' she says heartily. "I

mean, shit, let's face it. How long can they all survive?" We laugh. How does she

handle the loss? "Well, I'm sort of fascinated by what they're doing. I think they're on to

something extraordinary. Believe it or not, Bella comes to me. Colin comes to me!" she shouts

then adds, "He really does."

MacLaine recently finished a film that marks her directorial debut, Bruno, which stars Alex Linz,

Kathy Bates, Gary Sinise, Jennifer Tilly, Brett Butler, Gwen Verdon, and Maclaine. It's the story

of a boy with a troubled background who escapes by dreaming of becoming an angel. When his mother

and grandmother fall ill, the boy reveals that his true talents lies in healing those around him.

"Colin came to me while directing. He wasn't the only one. I'd call on Bob Fosse, Hitchcock,

and Willy Wyler." She props her feet up on the coffee table and folds her arms. "As far as

I'm concerned, nobody dies. They just change form." She misses Colin but justifies, "He

needed to go, so that's the way he went." To grieve is not part of Shirley's reality because death

does not represent loss for her. "It feels like they're onto something that is so much more joyful

than this. No matter how happy they were here or what they were doing." Barely finishing the

sentence, she inquires of Tim, the A&U photographer, what he is doing. He is setting

lights for the shoot. She doesn't miss much. She immediately refocuses. "I miss the

things that those people and I had together. But on the other hand, they've gone on to something

so much greater, that I have to think about them, not me," she says unselfishly. "I don't agree

with funerals. I like wakes, a lot of food, a lot of wine, and celebrating that they are onto the

next level that I'm not apparently ready for," she chuckles.

In 1994, when Shirley told her ailing mother, who lived in the apartment below, that she was leaving for

Baltimore to film Guarding Tess, her mother's eyes lit up. It didn't register at the time,

but Baltimore was a milestone for her mother. It's where MacLaine's parents met, where they conceived

Shirley, and where her father died. About one month later, Shirley received a call from her mother's

nurse, "Your mother just took her last breath." When she hung up the phone, the security alarm

clanged in this rented house where she was staying. Shirley had not set any alarm and didn't even

know where it was! Then she heard her mom say, "Go to the second bedroom and turn it off.

That's where the alarm is." Shirley did. Her mother spoke to Shirley in her mind, through

feelings, not words. She then drove to her old family home in Virginia. Once inside, her

mother directed her to an old cabinet where a letter was addressed to Shirley and had been written

twenty-five years earlier. As she writes in her latest book, My Lucky Stars, "The letter

had to do with my daughter and husband. Mother was warnig me about certain things. I broke

down and cried. Had I understood that letter twenty-five years before, it would have altered the

course of my life." Shirley gently whisks her long bangs from her eyes, looks steadfast, and says,

"So don't tell me that people die."

In 1994, when Shirley told her ailing mother, who lived in the apartment below, that she was leaving for

Baltimore to film Guarding Tess, her mother's eyes lit up. It didn't register at the time,

but Baltimore was a milestone for her mother. It's where MacLaine's parents met, where they conceived

Shirley, and where her father died. About one month later, Shirley received a call from her mother's

nurse, "Your mother just took her last breath." When she hung up the phone, the security alarm

clanged in this rented house where she was staying. Shirley had not set any alarm and didn't even

know where it was! Then she heard her mom say, "Go to the second bedroom and turn it off.

That's where the alarm is." Shirley did. Her mother spoke to Shirley in her mind, through

feelings, not words. She then drove to her old family home in Virginia. Once inside, her

mother directed her to an old cabinet where a letter was addressed to Shirley and had been written

twenty-five years earlier. As she writes in her latest book, My Lucky Stars, "The letter

had to do with my daughter and husband. Mother was warnig me about certain things. I broke

down and cried. Had I understood that letter twenty-five years before, it would have altered the

course of my life." Shirley gently whisks her long bangs from her eyes, looks steadfast, and says,

"So don't tell me that people die."

"The greatest love you can give someone is allow them to feel they have the freedom to go. That's

their free will. I firmly believe we all go when we want to, and we choose the ways we want to go

because whatever lessons there are in that disease, that's how we go. To allow them their own

destiny, and the end of this earthling destiny, to go on to something else. This is the greatest

love you can feel for someone. So why do you cry?" she asks with a lilt in her voice.

How does she feel about assisted suicide? "I think everyone should have the right and the choice.

It's very important. When somebody says, 'I'm sick. Don't put me on tubes. Let me

go,' I will honor that. And I have had the experience. How dare anyone make that a political

issue," she says with distaste.

Many PWAs have been known to make such statements as, "I am happier now than before I was diagnosed," or

"I appreciate life better and enjoy the moment more." Shirley remarks, "All of my friends who have

been through this demise of physical existence through AIDS have said that. I'm trying to think of

one that was angry." She can't. I mention Elisabeth Kübler-Ross' theory of the five

stages a person goes through to cope with loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

She looks slightly stunned . "I was just thinking of her! She's the only one who's

angry." Shirley hesitates then says in a slow cadence, "She hasn't read her books." She

furrows her brow, looks down, and ponders shortly. "I don't know what Elisabeth's problem is.

Now, I have to be fair. She might be bitter because it's a slow death. And she might just

want to go and can't."

In an interview several years ago, MacLaine talked about the metaphysical interpretation of the AIDS

virus and suggested that AIDS tends to infect "people who don't feel they are within the mainstream of

society. They are people who feel a sense of not belonging, of being unloved. And it

doesn't just apply to AIDS; it also appliles to cancer—or any disease, for that matter.

Being out of touch with the center within yourself, buying into bigoted propaganda—which this

society is so full of. Disease itself is just what it says: a disease. The thing that's

difficult to accept about this theory is that it sounds as though it's placing the blame on the patient.

But, on the other hand, it empowers the patient if he or she will take more responsibility for

what's going on with them instead of handing it all over to the doctor."

MacLaine feels Clinton has made some powerful statements, but she is skeptical about the implementation

of them. "The government needs to face the male chauvinism and face the homophobia. And they

have to face it in a big way. Millions," she corrects herself, "Billions should be spent on this

research. And it's not. It sort of makes you wonder if they're just letting it happen.

Look at these figures for God's sake. It's on the front of Newsweek magazine—forty

million orphans in Africa due to the [AIDS] death of the parents. For goodness sake, what are we

talking here?" she says firmly with bitter disappointment.

"And the greatest rise in AIDS deaths is in heterosexual teenagers!" she says while sweeping her bangs

from her eyes again. "The gays were responsible. And the one thing AIDS did was make the gay

community a very organized and powerfully evolutionary survival sector. It's a voting bloc.

And you know once you get that power, use it," she says enthusiastically.

MacLaine believes that nobody is truly doing enough in the battle against this epidemic, including the

entertainment community. "I don't know how many people are using condoms, but I honestly think that

sex education should be part of what we, as celebrities, should be doing. We can't just rely on the

Rosie O'Donnells and those wonderful people. The Surgeon General should be talking about this.

It should be possibly motivated by Americans in the Third World." Shirley worked with family

groups in India to prevent overpopulation by teaching them how to use condoms. "You can't say Mister,

come up here and let me show you how to do it. So I used a pole, took a condom and rolled it down on

the pole. The next morning everybody's hut had poles in the ground with condoms rolled downover them!"

she says bursting with laughter.

MacLaine believes that nobody is truly doing enough in the battle against this epidemic, including the

entertainment community. "I don't know how many people are using condoms, but I honestly think that

sex education should be part of what we, as celebrities, should be doing. We can't just rely on the

Rosie O'Donnells and those wonderful people. The Surgeon General should be talking about this.

It should be possibly motivated by Americans in the Third World." Shirley worked with family

groups in India to prevent overpopulation by teaching them how to use condoms. "You can't say Mister,

come up here and let me show you how to do it. So I used a pole, took a condom and rolled it down on

the pole. The next morning everybody's hut had poles in the ground with condoms rolled downover them!"

she says bursting with laughter.

Why has AIDS manifested now? "With the universality of the problems of promiscuity," she swiftly

responds. "The soul does not recognize heterosexuality or homosexuality. In fact, the soul

is androgynous. I talk about this in my new book. So the whole point of what you manifest in

your body basically is a balance of masculine and feminine—yin and yang. It doesn't make you

aware of both the feminine and masculine energies balanced in a way that you are sensitive to the yin and

the yang. And I have this sense that because we are so screwed up about sex and about promiscuity...."

She doesn't finish her thought because the phone rings. She loudly chortles, jumps up, takes

the call in the next room, and exits with elation of a young schoolgirl waiting to hear the scoop.

In a few minutes, she returns and plows right in. "Through promiscuity you are diverting the real

spiritual experience of a relationship in which you will find out more about yourself. So if you run

around being promiscuous, I don't give a crap if you're homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, or you like a

lamppost. If you stick to one lamppost," she grins, "you;re going to know more about yourself if love

is there. And I think maybe there's a universal message that we haven't understood. That

through love of one person and the sense of experiencing the balance of what the soul is," she pauses for

effect, "health results." Shirley shifts and crosses her legs. "And why do we feel we need to

have all these partners? I never thought I'd say this, because I've been one of these sexual freedom

persons, [although] I was never promiscuous. It got all tied up with religion, and the sense that you

can't really be a good partner unless you suffer and deny the pleasure you would desire. And I'm

saying the desire should come from wanting to be further in yourself and knowing who you are seeing in the

mirror," she says poignantly. MacLaine uses words like colors, as though she was Cézanne

gently brushing pigment on the canvas—precise and deliberate.

How did her inner journey and exploration into metaphysics affect her choice of character roles?

"I won't do anything violent. I wouldn't be comfortable with that. I'd be comfortable

with anger, rage, coming out of something that the character I'm doing needs to express." She mocks

her character, Aurora Greenway in Terms of Endearment, "Give my daughter the shot...!" What

a treat to see a reprise of Aurora Greenway from a front row seat!

Shirley looks out at the ocean and comments on the school of dolphins. She revels in the moment.

"Everything is really right with the world. But what's wrong with our perceptions is that we

don't look within ourselves to figure out why we're doing what we're doing. Like the only journey

really worth taking"—she elongates "really" as if holding a musical note—"is the one within

yourself."

Shirley gets up, and says reluctantly, "Now I have to do this thing called 'posing'?" She lets out

a sigh of discontent. The photographer is ready to shoot. "Can you talk to me while I'm doing

this?" she asks. In between the indoor and outdoor shots, Shirley briefly mentions how skinny many

of the girls looked at the Golden Globe awards. When finished, she grabs the phone and calls her masseur.

She hangs up, and we walk to the door. As she hugs each of us, I ask her how she would like

to be remembered. She replies, "As still being alive!"

Back to Top

|