|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

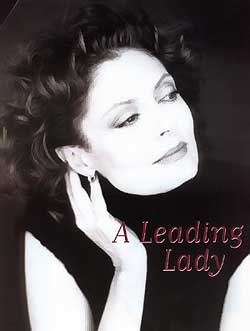

Photography ©Courtesy of Nigel Parry |

Over Breakfast, Susan Sarandon Chats with A&U's Dann Dulin About Her Many Roles—Actor, Mother, Friend, AIDS Activist, and Humanitarian. "Choreographers, actors, directors, artists, designers, poets, writers, you name it. We have just lost a generation of creative people—sensitive, funny, creative people. The world's a lot grayer now. AIDS just wiped out a lot of amazing people who would have contributed to God knows what, not just to may life, but to everybody's. It certianly meant that we would sober up a lot earlier than we might have in dealing with the loss of friends," Susan Sarandon says solemnly over breakfast at the Hotel BelAir in the ritzy hills of Los Angeles, her place of choice to hold the interview. When I meandered into this airy, elegant-yet-comfy hotel restaurant and the maitre d' ushered me to a corner table, I was surprised to find Sarandon waiting for me. Usually, I am the one waiting. She was reading Variety and didn't see me approach. As I passed a full-mantled roaring fireplace that illuminated the table, I quietly called out, and she greeted me with a welcoming smile. I instantly was captured by her warmth and down-to-earthiness. Susan wears black pants, a semi-dressy tank top, and a diamond necklace. Her face is au natural. No Makeup. This fifty-six-year-old youngster looks ravishing. The woman seems practically ageless. She had just returned from a workout at the hotel gym, though she's not staying in the secluded, storybook-like hotel but nearby with a friend. She explained that she called ahead to clear it with management to use their facilities (movie stardom has its perks). As she spoke, my mind flashed with memories of this star's many films, among them, Cradle Will Rock, Atlantic City, The Client, The Tempest, Bob Roberts, Bull Durham, The Witches of Eastwick, Thelma & Louise, The Hunger, and the incomparable, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, in which she was initially traumatized to sing. She has been nominated five times for the Oscar, and she took one home in 1996 for her performance as a nun who counsels a death row inmate in Dead Man Walking. Sarandon's first film was Joe in 1970 with Peter Boyle. Since then, she's appeared in over fifty feature films.

Like so many of us, Sarandon has witnessed the deaths of many of her friends and co-workers to AIDS. Unlike many of us, she has been able to transform her grief and sense of injustice into a passionate and active commitment to a wide range of causes, including HIV/AIDS. Two years ago, she visited Africa as a UNICEF Special Representative; in 1996, she helped found The HIV/AIDS Human Rights Project, which tackles AIDS discrimination; and in 1993 she and partner, actor/director Tim Robbins, stopped the Academy Awards stone cold with their plea on behalf of HIV positive Haitian refugees who were being held by the U.S. government. This commitment extends to her other roles, both in the movies and at home, as well. Now settled in, Sarandon continues to recall the early years of the plague. "It seems like a long time ago...it wasn't even identified. People were talking about the 'gay center,' " Susan's voice trails off in thought. She was appearing off-Broadway in Estremities, an intense drama about rape and revenge, and had invited an actor friend, with whom she had worked previously, to see the show. After the performance, he didn't come backstage. "I thought maybe it had been too disturbing for him. A short time later, he died of AIDS. Then I learned that the reason he hadn't come backstage was because of his appearance. He would not meet with people face to face because he was so ashamed," she pauses. Sarandon looks down a bit, and quietly adds,"—and suffering so much." She looks at me intently with distress. "Oh my God, to be sick and on top of that to deal with the stigma of it." As the waiter hands us menus, Sarandon explains how grief was transformed into action: "Shortly after my friend's death, New York had the first demonstration for AIDS awareness. The march went from Sheridan Square down to City Hall. I think there were only ten other women. It was all guys. I remember they asked me to speak and I just talked about my friend and why I was there. The thing that stunned me was that it wasn't in the news, didn't even get in The New York Times—and there were hundreds of people there! And that made me realize just how tough it was, and how tough it was going to be." She shakes her head affirmingly, and sighs. Those early years were tough, and horrific, and unthinkable. Most of us witnessed tragedy and had to confront it. I ask Susan how she dealt with the loss on a personal level. "I don;t know," she immediately replies gazing out toward the sunny patio. "When I look back on how I dealt with someone dying twenty-five years ago, I realize now that I was trying to find my way. I wasn't very helpful, really. I regret that. I did the best I could but I was younger and I didn't have the experience. We were all teaching each other, trying to figure it out. I think now I'd be a better guide. I think when you're dying you need..." She stops and searches for the word. "A maitre d'. You need a maitre d' at your death. Maybe someone who is not necessarily a close friend of the family but who can take those phone calls, deal with things and make the person comfortable. Some people are really amazing at it; they just rise to the the occasion," says Susan, admitting that she has not been a maitr d', though she has had friends who have assumed the role. In the role of actor, Sarandon has brought her HIV/AIDS experiences to the characters she has chosen. Stepmom initially piqued her interest because of all the people she knew who were fighting to live with HIV in the days before the cocktails. The 1992 film Lorenzo's Oil mirrored Sarandon's frustration at that time with the government's dilatory process for approving new AIDS drugs. The anti-convulsive drugs were available in other countries but couldn't get into this country. "AIDS was still such an unsympathetic cause and the film was the perfect way to explore these issues—a child at-risk from something that he didn't deserve. It was about the process by which new drugs are tested, about who has the patent, and who will make the money off of it," notes Susan. Off-screen, Sarandon plays a crucial real-life role. In 1999, she was appointed as a UNICEF Special Representative and the following year she traveled to Tanzania in eastern Africa. Originally, she was supposed to go to Cambodia and address women's issues, but when she heard of the tragic situation in sub-Saharan Africa, she changed her travel plans. AIDS is the leading cause of death in Tanzania, with sixty percent of HIV infections occurring in ages fifteen to twenty-four, and presently there are over a million orphans. What did she encounter? "In a lot of these countries the thing that strikes you is that there's just as many people dying from bad water and malnutrition. There are so many orphans. So much of it has to do with education. The fact is, it seems to take root in populations that people see as disposable. That's why the money isn't spent, and why the education isn't there." Sarandon ws so appalled to learn that a very high percentage of Tanzanians had no clean drinking water (women walk five hours a day just to get water and many children die from dysentery), that when she returned to the States, she and a gym buddy threw a "mini-benefit" to raise money to dig water wells for the Tanzanians. They called it Dig A Well. A friend donated the use of his restaurant for the benefit, Susan called some "high roller," and she got a guarantee from UNICEF that the money would specifically go to Tanzania for this purpose. One well costs two thousand dollars, and presently, there are about fifty wells installed. Their event made over a hundred thousand dollars. "People gave a lot. A few came through with some large sums, and the rest were just people giving money to buy wells. I've had people ask me when are we going to do it again. It's so simple, so practical," she chuckles and shrugs, indicating that she'd like to soon return to Tanzania and visit the wells. However, this fall Susan has a tight schedule promoting her three new films: Moonlight Mile, with Dustin Hoffman, Igby Goes Down with Jeff Goldblum, and The Banger Sisters with Goldie Hawn. The waiter brings our food. Splashing some red salsa on her scrambled eggs, Susan then sprinkles salt in her hand, and onto the eggs. She appears to be a conscientious eater—not even ingesting any carbs.

Sarandon's efforts don't go unnoticed. With her svelte, youthful figure it's difficult to believe that she is a mother of three. And being a mom is her proudest role. Susan's daughter Eva, seventeen, (pronounced Evva) with Italian director Franco Amurri, appears in Sarandon's new movie, The Banger Sisters. For fourteen years, Susan and Tim have been coupled (they met on the Bull Durham set and together they have two boys: Jack Henry, thirteen, and Miles Guthre, ten. Their home in New York. Family has always been number one to Susan, probably because she comes from a large one herself—nine siblings. Born Susan Tomalin, she grew up in Edison, New Jersey, in a family of Welsh-Italian descent. Her upbringing was conservative and Catholic. She attended parochial elementary school and later, graduated from Catholic University in Washington, D.C., where she met her one and only husband, Chris Sarandon. Having a mother as active and involved as Susan, it's no surprise that her kids are hip on the latest AIDS data. Sarandon knows that education is the key to AIDS prevention, and she's alarmed about the recent statistics that indicate a rise of HIV-infection among teens. "You know, if I were on the podium in front of an auditorium of kids , I would want somebody like Eminem with me. I'm not a spokesperson for teens. I think you have to approach them with hip, cool people who can communicate the idea up to, and people who are HIV-positive who never imagined it could happen to them," she stresses, waving a fly out of her face. "You have to have conversations with boys and girls way before it's condom time. Conversatoins that have to do with making somebody comfortable with who they are, and therefore they feel comfortable with saying what they need. It's all about self-esteem. Little girls aren't going to be promiscuous if they're feeling good about themselves. They're not going to want to be in an alley giving a blowjob. I think what we have to do with our kids is to make them understand that they deserve joy, happiness, and to be healthy—that their futures are full. If you don't have any belief in your future, then of course you throw away the present." Sarandon's cell rings. She answers it, and talks cautiously, aware that my tape recorder is still running. It sounds like a movie deal is in the making. Quickly ending the call, we return to business at hand. "People are just exhausted with it, " she laments as she reflects on the current AIDS apathy. "People have been asked to give a lot. I think hey don't know really where to focus. Certainly, 9/11 took a bite out of everybody's pocket book and emotions, and people became very focused on the immediate loss of those lives." Her voice is modulated to a soft tone. She takes a sip of English Breakfast tea, and adds: "It's really hard these days. So many people are asking for money for so many things. I don't think people have the same sense of immediacy about the AIDS epidemic. The communities that are really hit, like the Hispanic and black ommunities—again, it's people who are voiceless, in a way, and they are seen as being disposable, just like the gay community has been. If it were something that really hit the Senate Majority people, they would pay attention a lot quicker!" Sarandon's outspokenness and eagerness to change the status quo resulted in her being arrested on several occasions during protests. But, she's dedicated to exercising her First Amendment rights. With an intelligent body of work, a sense of duty, and a strong arm for equality, I compliment Susan on her rebel-rousing role. "There are a bunch of people who do this day in and day out. I'm just like an entrepreneur," she says modestly. "Every single day of their life, there are people just trying to push some huge boulder up a hill in some form or another. They are the people who really inspire me and are at a grassroots level where change will happen. Change is going to happen because people at the bottom demand that it happen, and those are the people that are really great. It's not going to happen from the top, not from Bush." She leans slightly forward, changes the subject momentarily and this seems to be classic Sarandon—deflecting attention from herself in order to change the current state of affairs: "What is the Bush administration doing anyway in the AIDS epidemic?" she asks vehemently. "I just see all the money going out to military spending these days for security systems that, I'm sorry, didn't work the first time, so I don't know what they think is going to happen now." Briefly collecting her thoughts, Sarandon returns to the topic: "The basis of my activism, which are basically the muscles that my profession develops, is imagination and empathy. I mean, if you can empathize with a woman who loses her children, or who's living on the street, or a guy who's getting thrown out of his apartment because he's sick, or whatever, you empathize. If you see that person, it's not a question of 'them' as opposed to 'us'. So how can you not do something?" she pleads with those famous tender brown eyes. "You can't live with yourself. It's really just a question of self-respect and survival. How can you look your kids in the face and say you knew about something; that you had the power to do something, and not do it? You have to live your life in a way that you would hope they would feel some sense of responsibility, as well. So, it's completely self-serving—it's not altruistic. I don't have any choice really." Well, like all of us, she does have a choice. Sarandon's articulate, sharp, and, yes, she even possesses that indescribable mystique that we seem to imprint on all of our Hollywood stars. But she's used these as tools to capture people's very limited attention to illuminate critical issues they would otherwise ignore. Susan is truly one of the leading "leading ladies."

|

| Return to CELEBRITY ARTICLES |

| ©2009 Dann Dulin, All Rights Reserved | New Site Design: Nancy Rosati |