|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

With

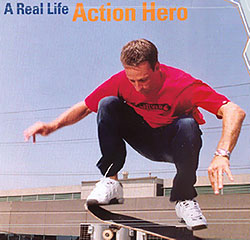

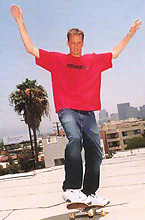

a burst of SPEED I don't know anything about skateboarding, and never wanted to. It took a lot of convincing for me to agree to interview Tony Hawk—arguably the most famous and influential skateboarder in the world. When I spoke to my forty-seven-year-old, Ohio-based sister, she screamed like an adoring fan, "You're going to interview Tony Hawk?!" I asnwered with, "You mean you know who he is?" She restorted derisively, "You don't?" From thereon, I further checked into this Superhero and even read his best-selling 2000 autobiography, (Hawk: Occupation: Skateboarder). What surprised me the most was that he lists skateboarding as his occupation. The more I read, the more I began to see him as a humanitarian rather than a sports figure. Hawk and I meet on a delightful sunny afternoon in West Los Angeles. Though presetnly on the road with Tony Hawk's Gigantic Skatepark Tour, he has a couple of free days. When Hawk appears at my door, I think that he is a neightbor or a deliveryman. A towering six-foot-three-inch man takes me aback. I had assumed skateboarders were short—that's how unsavvy I am. Tony drove up from his home, which is located on a lagoon in the coastal village of Carlsbad, California. He's clad in slightly oversized jeans and a white T-shirt. Though tall, he has a very slender frame. He totes a red backpack and sports Hawk tennis shoes, which are floppy and loose laced. (Tony owns Hawk Shoes, and Hawk Clothing, though the kids' skate wear was acquired by Quicksilver in 2000). Tony is a Cheerios-type guy–all american boyish looks, down-to-earth and sturdy stock. But there is nothing cheery about AIDS. Hawk's drive to overcome the inherent risks of the sport to achieve his personal best, combined with his concern for his most ardent fans—America's youth—has led him to his active role in the battle against AIDS. Tony wants kids to have an opportunity to achieve their own personal best, despite the profound and deadly health risks they face as they begin the inevitable exploration of their emerging sexuality. And Tony hopes to do just that. "I care about how people perceive not only the disease, but the gay community. Not that it's like my Big Cause but I feel like there is a lot of misunderstanding and that people automatically assume that AIDS is some sort of punishment. I've heard that spoken before and it just seems so unreal that one could think that," declares Hawk, as his legs, which appear to make up most of his body, become slightly restless, and his feet arch upon his toes. He has friends who are HIV-positive, and people generally don't know why they are. If they did know, Tony believes that they would be victimized by the false assumptions people still hold about the virus. This agitates him, as he also was discriminated against. At school, he was an easy target for bullies, with his small "skeletal" frame and "geeky" looks. Early on, he was tagged as "gifted" by a psychological evaluation, though throughout his school years he felt like an outcast. Tony's brother gave him his first skateboard when he was nine. "When I found skating, I finally found something I could do at my pace. When I was growing up it was all about baseball and basketball, and if you didn't do well in those you might as well not play sports," says Tony in his soft, low-keyed voice. "I was so slow in both, and I never felt like I was improving. When I started skating I felt like I was getting better every time. I had my own style and could still be accepted." While fans mobbed him for his autograph, he was still being teased at school. Nonetheless, Hawk was determined to be the best skateboarder. After practicing obsessively, he began entering contests. By the age of twelve he had his own sponsor, Dogtown; at fourteen he was a pro; at seventeen, he bought his first house. Then in the early nineties, skateboarding tanked in popularity, which plunged Hawk into serious financial straits. For several years he spinned, flipped, and backslid, but this was no skateboarding competition. In time, skatebaording made a comeback and Hawk ascended back to the top. (It seems Tony has learned from his journey, as throughout the interview he appears wrapped in an inner peace; anchored in self-assurance). At this point, Tony shifts the focus of our conversation away from his own personal history, back to AIDS and is more intent on sharing his passion for protecting his millions of fans as well as his three sons; Riley, from his first marriage; and Spencer and Keegan, with current wife, Erin. When his boys reach adolescence, true to character, Tony plans to be straightforward, factual, and honest with them about AIDS. "That's one thing my dad wasn't really into. He didn't like being upfront especially with matters of sex. He came from the era where you don't talk about that stuff," whispers Tony with a side smile. From the beginning, Tony's father was his most avid fan. His father, frank, hauled him up and down the coast to skate contests, and even built skate ramps for Tony. In the eighties, Frank Hawk founded the National Skateboard Association. "My dad was one of those guys you always see at Home Depot wearing a baseball cap, a toothpick hanging out of his mouth, a worn plaid shirt with small tears in the elbows, and work pants," Tony affectinately recalls in his autobiography. Sadly, in 1995, Frank was diagnosed with cancer and within six months, he was dead. How did Tony deal with the loss? "I don't get too spiritual in these matters, but I couldn't have been a pro skater if it wasn't for my dad's support in the beginning. I will do the same for my kids. That's how I carry on his tradition—by being involved with my kids." Hawk commits his time to several kid-oriented charities including The Tony Hawk Foundation, which supports organizations that build quality public skateboard parks. In June, Tony taught guests skateboarding skills on the specially built half-pipe at Elizabeth Glaser's Pediatric AIDS Foundation annual carnival fundraiser. He participated last year, too. "Skateboarding is not so much about being a daredevil; it's mostly just to push conceived limits. It's not like I just want to go and cheat death. I want to go and figure out what's possible that people may think is not possible. Getting hurt is sometimes part of the process, but it's not usually the motivating factor. I'm not Evel Knievel," he chuckles as his hands cup the back of his head with elbows in the air. This rather shy fellow shines when he talks about his sport. "If Evel doesn't make what he sets out to do, he will die. In skating, it's more calculated. You've got to have the confidence to do what others think is impossible, but also know that you can get out of a dangerous situation. You challenge yourself." This reminds me of what Hawk said in his book: "Skating is not about winning, it's about skating the best you can and mutual appreciation." At the Summer 1999 X Games, Hawk made history when he successfully completed the 90—a trick that thrusts him twenty feet into the air for two and a half full body rotations. He is the only skateboarder who has ever pulled this off. Hawk has placed first or second in every event (over a hundred), taking home six gold medals in the ESPN-X-Games, and in 2001, he received the first ESPN Action Sports Achievement Award. Tony Hawk's Pro Skater video game, released in 1999, sold more than two million copies in the first year. The fourth edition has an October release date. This fall, Tony will hit the road for six weeks (thirty cities) with the Boom Boom Huck Jam, a high-explosive stunt and music extravaganza that includes skateboarding, BMX bikers, and Motocross. And several times a year, Tony does commentary on ESPN. Though retired from competition, thirty-four-year-old Tony stays very busy, and he still skates everyday. As we wind down, I realize that there is much more to skateboarding than I ever imagined. Now being skateboard savvy, I know that Stalefish, Ollie, and Fakie is not a hot new rap group. They are tricks of the trade, and Tony has mastered them all. He has even invented more than eighty tricks of his own, including the Kickflip McTwist, Madonna, and the Stalefish. After years of being dismissed as a mere novelty or fad, skateboarding has become a respected sport, in large measure because of Hawk's contributions. While I'm not planning to hop on a skateboard anytime soon, Hawk's enthusiasm is infectious and listening to his adventures has really piqued my interest. But alas, he is due in the ESPN studio within the next hour. Before he departs, he comments that the smartest way to reach kids about AIDS prevention is to present them peer-related statistics, not through celebrities they may admire. "Teens, like the type of kids who are skateboarding, are exploring their sexuality," he pauses for a moment, then continues: "and they don't realize what kind of risk they're running if they're out having unprotected sex." Tony is very concerned that the word is not getting out to adolescents and that Americans are becoming more passive in the fight against AIDS. "There was a huge support for the victims of September 11, yet there are still kids who are sick with HIV and AIDS. The events of September 11 don't stop (the spread of) AIDS, and it doesn't mean we need to shift charities all of a sudden. The AIDS epidemic affects everyone, and it definitely could happen to you—and that bothers me." |

| Return to CELEBRITY ARTICLES |

| ©2009 Dann Dulin, All Rights Reserved | New Site Design: Nancy Rosati |

In

this spirit, Tony got involved with the campaign Until There's A

Cure earlier this year. He joins a bevy of other celebs that

wear The Bracelet, among them, Destiny's Child, Many Moore, and Kevin

Bacon. "AIDS is not the news buzz anymore and it is still

very apparent," he says thoughtfully, seated on the sofa. "HIV

is still growing in numbers and it's not going away. Just because

you don't read about it on the front page doesn't mean it doesn't

exist anymore. There still are a lot of stereotypes that are

connected with HIV and AIDS and people just don't realize how widespread

and how much at-risk everyone is. There are HIV-positive infants..." His

voice trails off without finishing the sentence, and he shakes his

head pondering the tragedy of what he has just said. "Sometimes

people just choose denial as a way to avoid reality, or they twist

a situation to match their beliefs.

Someone needs to change their minds!"

In

this spirit, Tony got involved with the campaign Until There's A

Cure earlier this year. He joins a bevy of other celebs that

wear The Bracelet, among them, Destiny's Child, Many Moore, and Kevin

Bacon. "AIDS is not the news buzz anymore and it is still

very apparent," he says thoughtfully, seated on the sofa. "HIV

is still growing in numbers and it's not going away. Just because

you don't read about it on the front page doesn't mean it doesn't

exist anymore. There still are a lot of stereotypes that are

connected with HIV and AIDS and people just don't realize how widespread

and how much at-risk everyone is. There are HIV-positive infants..." His

voice trails off without finishing the sentence, and he shakes his

head pondering the tragedy of what he has just said. "Sometimes

people just choose denial as a way to avoid reality, or they twist

a situation to match their beliefs.

Someone needs to change their minds!"  Today,

Tony has strong paternal feelings for his fans, and wants to protect

them, as he would his own kids. This is why he advocates condom

distribution in schools. He cops a funny face. "If

you don't pass condoms out then kids won't be promiscuous," he

mocks, then blurts with a weary sigh and expressive hands, "That

is totally wrong!" He looks at me in disbelief. "In

some ways, this may be a bad analogy but in skateboarding, the city

officials tell kids that: they can't skate here; they can't skate

there; not on the street, not on private property. Yet they

won't provide a place to do it. And they think that's going

to solve the problem by just telling them 'no'. But the kids

are going to skate regardless, so you might as well provide a place

for them to do it," he demands. Then he sums up:

"Kids are going to be out having sex anyway, so let's keep them

safe."

Today,

Tony has strong paternal feelings for his fans, and wants to protect

them, as he would his own kids. This is why he advocates condom

distribution in schools. He cops a funny face. "If

you don't pass condoms out then kids won't be promiscuous," he

mocks, then blurts with a weary sigh and expressive hands, "That

is totally wrong!" He looks at me in disbelief. "In

some ways, this may be a bad analogy but in skateboarding, the city

officials tell kids that: they can't skate here; they can't skate

there; not on the street, not on private property. Yet they

won't provide a place to do it. And they think that's going

to solve the problem by just telling them 'no'. But the kids

are going to skate regardless, so you might as well provide a place

for them to do it," he demands. Then he sums up:

"Kids are going to be out having sex anyway, so let's keep them

safe."